ABOUT US

Our History

Calle San José + Calle Luna

Old San Juan has a rich history as an important Caribbean Spanish settlement in the sixteenth century. San Juan Historic Site is a designated landmark since 2013 and the most distinguished resource in Puerto Rico. The resource includes the old city, fortifications and surrounding bastions as protection. Military planning determined urban development in colonial cities of the New World. As a result, the fortifications and bastions significance relies on characteristic techniques of European military architecture construction that were adapted to Caribbean conditions. Today, Old San Juan fortifications represent the finest surviving example of military engineering built during the Spanish Empire. In addition the old city has transcended its military significance to become an important signifier to the people of Puerto Rico. The forts have become a constant symbol in the city’s landscape to be enjoyed as an intrinsic part of the topography.

Building Design Principles for Old San Juan

Starting with the street view, facades in Old San Juan define the volume with a solid appearance and serve as protection establishing the close relation between inside and outside. Openings for doors and windows in the façade composition were typically emphasized with abstract moldings taking advantage of the sun’s contrast against the reliefs as a design element. The building’s corners were protected in very early colonial construction for practical reasons since they got the most damage. The definition of the sidewalk did not exist in colonial times making this part of the masonry buildings especially vulnerable. Cornices appear in the 18th century as well as the indent at the roof line. Elements from classical architecture where interpreted in a simple way until 19th century when façade details become more ornate. The façade rubble masonry walls are traditionally thick since foundations were made shallow and the strength relied on outside walls for structural support. The thickness of the walls served as a fire retardant and helped control the outside climate by isolating heat. Various configurations of balconies in depths and sizes were the result of wood beams extension connecting façade walls with interior masonry walls for lateral support and floor structure. Balconies had a social meaning as well creating the opportunity for contact of the inhabitants with the street activities below. It allowed residents the possibility to see what went on in the city and be seen as well.

The hallway that connects the street to the interior patio is called a zaguán and is a recurring theme in Old San Juan. This receiving element gives interior spaces an elegant public access from the street. The building known as Casa de los dos Zaguanes at San José Street has a staircase placed in the middle of the space creating the two passageways. Stairways in Old San Juan are not very elaborate when compared with more opulent ones found in other Spanish colonies that enjoyed more wealth. Because second and third levels were added to the buildings later in the 17th and 18th century, stairs usually had to be accommodated to existing spaces. With the exception of colorful ceramic tiles on the risers and wood detailing stairs appear as a rather simple presence inside the buildings. There is a variety of stair configurations as an outcome of being a late occurrence.

The roofs during early settlement era were finished with ceramic tile and were shallow pitched when houses were generally one story height. As the city grew vertically, roofs were designed to be flat and slightly leveled to collect rainwater. Roofs also served practical uses and additional space in the house. The water collected in them was directed through pipes inside the walls to underground cisterns called aljibes. Cisterns maintain the water clean and safe to drink at all times due to the inherent antimicrobial qualities of limestone material used for construction and to cover surfaces. The lack of water in the San Juan islet made it a necessity to have household cisterns in order to be a self-sufficient city in case of enemy attack and finding themselves under siege. The largest aljibes in Old San Juan are underneath El Morro and San Cristobal Forts capable of holding drinking water for the inhabitants in case of attack.

Concern about good sanitation and order was broad across European metropolis around the 19th century. Accordingly, authorities in San Juan at the time were taking measures to impart organization and hygiene to contest problems experienced by the citizens with overcrowding. Work started in 1890s for the supply of waste water drainage pipes under city streets. Before, all garbage and waste was deposited on the streets and cleaned at certain times by city employees.

The House at 106 San José Street

The first inscription for the property labeled “A” at the San Juan Deeds Registry books dates from the year 1881. It comes from volume 8 folio 114 of the San Juan Norte section. The property description refers to an urban house of number 14 at San José Street. Street names and house numbers for San Juan were changed around the middle of the 20th century so the number registered does not correspond to the one #106 used today. The house described at the time consisted of a ground floor leading to the second level. The building materials were described of masonry construction and it was covered with an azotea meaning that it was of flat roof. The house bounds on the side or to the north, with a property owned by Doña Carmen Romero. For the back property or to the west, it abuts a property said to belong to Don Lorenzo Rivera and the widow of Martínez Calvo.

The first inscription of the property appears after inscription “A” in the San Juan Deeds Registry and dates from 1882. The building is described as designated with the number 14 located in San José Street and the corner of the Cathedral Alley, today Luna Street. Towards the right, at San José Street, the property borders with the property of Doña Carmen Romero. Before her the owner was the priest Don Francisco Borja Romero. The other neighbor property belonged to Doña Antonia Martínez, this house used to belong to the priest Don Valentino Urquese according to the inscription. Lastly, the south border of the building, what is now Luna Street, belonged to Don Francisco Acosta. Luna street is not mentioned in this inscription form 1882 therefore at this time the land, could have been private property. There is a building on the site by this time according to the registry book of 496.73 meters in size.

At the time when the Charity of San Idelfonso organization acquires the building, the loan debt on the property was made through San Francisco convent in the amount of 500 Spanish pesos recognized by the title presented and registered to the folio 310 number 894 of the 8th volume from the old registry book. The loan amount of 460 pesos, in addition to the interests in favor of the collections office of the Holy Cathedral Church’s treasury was inscribed in folio 7, number 19 of the 9th old registry book. The inscription from 1881 as it appears on the Deed Registry indicated that the estate did not appear registered previously by anyone. It meant that people had titles for their properties but did not register them. The Catholic Church emitted loans for citizens on properties acting as banks since according to the “Ley de Indias”, the church had allotted money to build churches and oversee the construction of the city. The case was settled at the Court of first instance of San Francisco District by clerk Don Esteban Calderón. Because of the mortgage obligation of 5,000 pesos in favor of the City Council of this Capital against Don Gavino Gamín and his wife Doña Juana Saint Just Quiñones, the estate of number 360 has been seized from them. Don Gavino and Doña Juana lack the title of registered domain on the property which prevents the final entry. Don Esteban Calderón inscribed instead this information and took preventive annotation for the suspension of the Court of San Francisco by expressed amounts.

The Deed Registry inscription provides a summary of the property’s history of ownership. On June 7, 1882 Don Jaime Agustín Milá, priest of the Holy Cathedral Church and resident of this city went to the Cathedral District City Jury of first instance claiming that the organization for the Charity of San Idelfonso’s was the owner of the property to date and operated in the building San Idelfonso’s Asylum. The meaning for an asylum then was an institution that helped the poor, housing them and educating them. The term did not mean what is known today as a place for mentally ill persons. Priest Agustín Milá argued in court that the property had been transferred to the religious organization possession from Don Gabino Gamiz and Doña Juana Saint Just the year before, in August of 1881. Evidence was shown to satisfy the claim that 106 San José Street was transferred by property deed notarized by Don Mauricio Guerra and from that date they have been in possession of the property as owners. It is described how Doña Juana Saint Just obtained the property from her father Don José Saint Just through inheritance and that he had purchased it from Doña María Rosario Quiñones. The information is said to be in Title Deed dating from September 26, 1829 where Doña María Rosario acquired the house from Don José Dávila when he left it to her according to his will and testament. This is the earliest date for information on the property from the Deeds Registry description.

Official notary Don Mauricio Guerra Mondragón y Mejías made The Title Deed in August 20, 1881 which consists of 21 pages explaining the details and information testifying to the property ownership, provenance and acquisition. The two parties present at the time of the Title Deed signing were Judge de Seras Oliva from the Court First Instance at San Francisco District and Don Jaime Agustín Milá priest from the San Juan Cathedral church representing the San Idelfonso House of Charity and Crafts by permission from the organization’s board president. The Title deed had the purpose of inscribing the property to their name and legalizing the transaction from public auction by which it was obtained.

On September 1st, 1874 the property was confiscated from Don José Laguna y Saint Just who was the representative of owners Don Gabino Gamiz and Doña Juana Saint Just a married couple who were absent from the Island. The couple owed money from the upstanding loan with the municipality at this time. As a result from the legal case against the couple, a public auction was held in 1879 to sell off the property. Don Claudio Monso was chosen as the person who had the best offer on the table for the property so it was apprehended to be destined for the San Idelfonso Asylum organization. Doña Juana Micaela Fernandina Saint Just was the only surviving daughter of brigadier Don José Saint Just and Doña Juana Quiñones according to his legitimate military will dated September 25, 1862. Don José’s official tittle was lieutenant general from the Infantry of Granada, 15th line with the charge of protecting the city of San Juan. Don Antonio María Aldrey was the War Justice Functionary officer who validated Don José Saint Just testament where he left all his material possessions to daughter Doña Juana except from 200 pesos he left to his slave in remuneration for her good services. The Infantry Coronel José Saint Just made the will for had been sick for ten years with an ailment that was advanced at the time of the will.

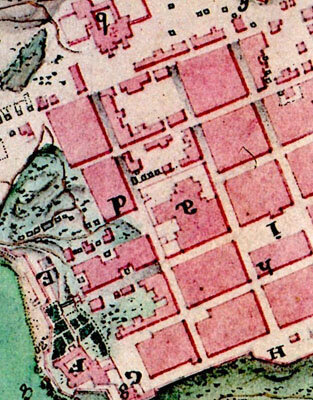

The daughter Doña Juana Saint Just had married Commander Don Gabino Gamiz and they inherited the described two-level stone house with roof tile at San José Street. During this time period, stone was a general term used to describe rubble masonry construction material as opposed to wood construction. The property as described in the testament copy from the Title Deed, bordered to the north with the priest Don Valentino Urquese, west with Don Vicente Pacheco’s succession and south with Don Francisco Acosta. The measurement of the property was 679 ½ Castilian Varas from east to west along a patio wall in a straight line to Pacheco’s wall. This measurement equals 5 feet 6 inches per one Castilian Vara and is equivalent with today’s measurements. This information is comparable with property lines clearly marked in Thomas O’Daly Plan of San Juan where the interior plots called corralones were divided with segmented lines indicating property boundaries. The hashed lines would later become dividing walls between houses on future consolidated blocks.

The building, once acquired by the Association of the Daughters of Charity of San Vicente de Paul de Puerto Rico used the property for educational purposes and the religious teachings of the Catholic Church on this and other two more properties in Old San Juan where they also ran charitable work. The second inscription from the Deeds Registry dates from 1895 and indicates that the property was used as the House of Charity of San Idelfonso. The Company of the Daughters of Charity San Vicente de Paul still is today an apostolic organization founded in France 1633 by San Vicente de Paul and Santa Luisa de Marillarc. The organization started missionary work in Spain in 1790 continuing the charity service in education, health, social work, elderly care and children shelter. In Puerto Rico, the foundation of the Company of the Daughters of Charity San Vicente de Paul dates from 1863. This organization occupied the building San José 106 from August of 1881 until May of 1960 and used it for asylum and education purposes. Another Charity Asylum form the same congregation of nuns was established according to documents from San Juan Municipal Works on December 10, 1879. This one was located at number 22 San Sebastián Street and the purpose was to shelter the poor that needed public charity since the amounts of destitute people on the streets was said to be increasing. The Daughters of Charity also directed various catholic schools in other towns of Puerto Rico around the year 1912. The towns they operated schools in were Coamo, Mayaguez, Ponce and Manatí. As for San Juan, they were in charge of three, the Colegio de Párvulos, San Idelfonso School and La Inmaculada School. San Idelfonso School is described as being dedicated to primary instruction, English language, embroidery and crafts. San Idelfonso School became the Seminario Conciliar founded in 1832 at the building next to the convent.

In May of 1960 The Association of the Charity Daughters of San Idelfonso sold the property to Industrial Development Company of Puerto Rico by way of Antonio Torres Fernández. The third level of the property makes its appearance in the Deeds Registry according to the inscription dated in 1967. Therefore we can deduce that by this date the third level was already built. The same inscription mentions that the property has a clause that the building was destined for tourist use, with a commercial restaurant and apartments. The property description from 1983 maintains the same size of 496.73 total square meters, however the boundaries change. To the north, the building limits with land of the Industrial Development Company of Puerto Rico. This means that PRIDCO bought the adjacent property as well. On the south it limits with Luna Street and lands owned by Vicenta Esteban, on the East by San José Street and by the west with property of Iván Aldrey and lands of Vicenta Esteban. The building has two levels and a penthouse that refers to the recessed third level with a total 8,867 square feet for the entire property. The first level has 4,760 square feet and the second level has 3,699 square feet according to the inscription.

Changes to the Property

In 1894, neighbors from San José and Tetuán Street filed a formal complaint against authorities for charges from a water connection that was unfinished leaving them without wastewater service. The citizens claimed that they weren’t connected to the drain system, yet they were charged for unavailable services. At least for these two streets of Old San Juan, the connection of individual houses to the main drain pipe was completed during the year 1893 according to the claim. The neighbors were dismissed from the payment until the work was finished.

The will and testament from Coronel Don José Saint Just in 1862 describes a piece of land that was sold to the Coronel in the amount of 6,500 pesos with all accesses and legal rights. This piece of land becomes part of the property 106 San José Street and is described as entering in a piece of the corral measuring 6 Castilian varas. The measurement and location coincides with the smaller patio belonging to the property. The writer also advises that there is a latrine belonging to the house close to a masonry wall room. This is written evidence confirming an archaeological excavation from 2005 when an old covered latrine was discovered.

In May 1952, the property was visited by F. Vargas, a Planning Board employee to assess the building and its conditions. At the time there were five apartments for housing on the second level and two commercial spaces on the first level. The third level had one family with guests so it is assumed the penthouse was built not long before this date. The Daughters of Charity proposed a completely new two story building of concrete and glass materials for commercial space below and apartments upstairs. The design was not harmonious with the Historic Zone and the permit was denied. Another project by the same engineer Carlos Lázaro dates from 1957 and proposes repairs to the second floor. Apparently the repairs were made to the building.

The file on property 106 San José Street at the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture reveals facts about projects and changes done more recently and up until 1962. Handmade drawings on the ICP San Juan Historic Zone Office show façade recommendations for this building dating from October 27, 1970. The perspective drawings from an unknown artist reproduced in photographic paper depict two options to be used for the second floor balconies on the building’s façade. Both options consisted of wooden balustrade one for single balconies at each door or a long balcony spanning three doors on each façade and a single balcony on the remaining door at San José Street. The drawings were guidelines to follow for future renovations shown below is the long balconies.

In 1970 a renovation project was completed were a number of features added to the building can be seen in place today. Arches were added to the first floor commercial area, planters were added to the side staircase and hydraulic tiles were changed for antique marble on the staircase steps. Four bathrooms were added to the already four existing ones for a total of eight bathrooms. The flooring material for the terrace and remaining floors was changed at this time from vinyl asbestos to ceramic tile.

A series of letters were issued from 1981 to 1987 about deferred maintenance on the property and illegal equipment and materials present and visible from the street. There were air conditioners at the façade and roofs over the penthouse terraces made of wood and cardboard. In response to the overdue repairs, design plans from March 1982 were presented by J. M. Ventura & Associates engineers and architects. The proponents for the project were Loíza Garden Developers intending to rehabilitate the building as Housing and Urban Development, Section 8 rental subsidy units. The total amount of apartments for the project was 19 with seven studio apartments, 11 one bedrooms and 1 two bedroom apartment. This project was completed and is how the property operated until the end of the 20th century. In the year 2000 an archival photo reveals the restored the balcony in traditional wooden balustrade with tejadillo or small wood and ceramic tile roof over the openings.

A renovation project in 2005 that was not complying with legal construction standards was left half completed. An archaeological monitoring report from May 2005 analyzed an excavation of a trench dug for a trench pipe five feet deep. The trench was mostly sterile however ceramic chards, ceramic tile, animal bone and seashells were found at the far end of the property. In addition, remnants of covered latrine were uncovered at the same place. This may be the privy described in the Title Deed records of 1881 because it coincides with the location and description given then. This is the second to last renovation done before the property is bought by José Santana in 2012 and the footprint could be recognized as found. The building was renovated to house a 20-room hotel and restaurant, the Decanter Hotel, which opened its doors on December 23, 2015.